Move FM Australian News

5 new Australian publishers are making defiant, weird, grass-roots books

Sep 19, 2025Share article

Print article

In the past year or so, three Australian publishing mergers happened within a few short months. Text Publishing, Pantera Press and Affirm Press were all absorbed into a larger company. Once a company has shareholders, like Penguin Random House and Simon and Schuster (which acquired Affirm and Text), the business is geared to generate the greatest return for them.

Meanwhile, the closure of 85-year-old literary journal Meanjin has drawn the ire of industry insiders and readers in Australia and abroad.

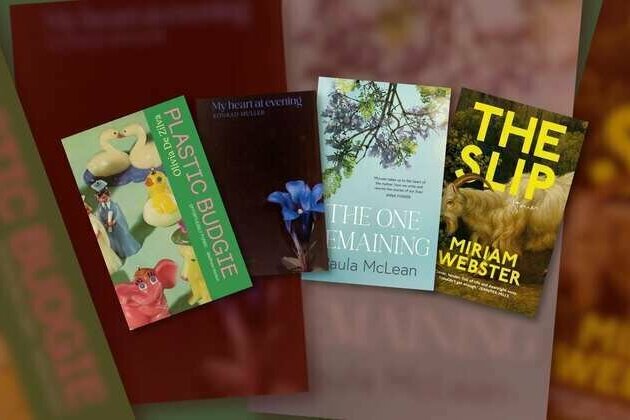

But there’s also some good news in the launch of five new Australian book publishers: Perentie Press, Pink Shorts Press, Evercreech Editions, Aniko Press and Bakers Lane Books.

Their new work includes short books, graphic novels, short-story collections, experimental writing and literary fiction. Two are launching with prizes for unpublished work: one (worth A$2,500 as an advance towards royalties) for a graphic novel; the other a $10,000 award for an unpublished work of literary fiction by an Australian woman or gender-diverse writer, co-judged by Stella Prize winning author Emily Bitto.

Three of the new ventures have set up outside of the standard duopoly for publishing: Sydney and Melbourne.

Brisbane-based Perentie Press, run by art teacher and author Bethany Loveridge and publisher Rochelle Stephens, is focusing on graphic novels – “particularly among young readers”, they told the Age.

Pink Shorts Press, founded by Margot Lloyd, former deputy editor of Griffith Review and senior editor at UQP, and Emily Hart, former publisher at Hardie Grant, is in Adelaide, where the founders met working at small publisher Wakefield Press.

So far, Pink Shorts is publishing fiction: a comic take on autofiction and a satirical short-story collection by debut authors, and two cleverly packaged editions of classic novels by Adelaide author and artist Barbara Hanrahan (whose art adorns the covers), with contemporary forewords. “Australian readers are keen for books that break the mould,” they told me.

Evercreech Editions, the Hobart-based brainchild of bookseller and author Adam Ouston, has similar aims. His vision is to provide “an outlet for the out of step, the weird, the boldly defiant, a home for the homeless” – which he calls “distinctly Tasmanian”. His first project is a literary novel by former Australian diplomat Konrad Muller, described by Robert Dessaix as “a glossy black cockatoo of a book”.

In each case, these publishers are the project of industry insiders.

In Sydney, there are new entrants too: Aniko Press, which has risen from a five-year-old literary journal, is run by writer and editor Emily Riches. Its first book is a “dark, feral” short-story collection by Miriam Webster, a Wheeler Centre Hot Desk Fellow and winner of the inaugural Kill Your Darlings Nonfiction Essay Prize.

Bakers Lane Books is launching with a A$10,000 manuscript prize. Founder and publisher Ginny Grant is creating two imprints, with a focus on “new voices and women writers in all their diversity”.

The money has to come from somewhere. Pink Shorts is running “Wordshops” to help “businesses streamline their approach to words”. They told me, “We’re used to working with authors to draw out their distinctive voices and cut unnecessary waffle, but it turns out those skills are invaluable to businesses as well (especially in the current age of endless AI [artificial intelligence] overwriting).”

Running such programs is one way to underwrite publishing books.

Initially, Pink Shorts is using the “savings” of its co-founders, but they told me, “there’s so little money in the book publishing business that some grants will inevitably be part of our future”.

Evercreech has also announced writing workshops – and its funding is coming from a “generous and silent benefactor“. Bakers Lane Press is “self funding“.

Perentie has “a little bit of seed funding“. Aniko’s funding isn’t listed on their website, but the early issues of their magazines have sold out.

There are other ways to fund operations, too: these include publishing books with primarily commercial ends to underwrite the more literary projects. Famed women-run publisher McPhee Gribble, founded 50 years ago, part-funded their publishing operations with information books for children called “Practical Puffins“.

In a country as large and sparsely populated as Australia, the first concern for any new publishing enterprise is distribution: getting books into bookshops – and into the hands of readers.

I asked the pair behind Pink Shorts about this. “Distribution was the single biggest factor we worried over,” they told me. “There are so few options for small presses, and they all take a big chunk of revenue.”

Publishers offer booksellers a discount of around 50% to sell their books. Of the 50% a publisher gets, as much as 30% goes to a distributor.

The only reason Pink Shorts Press can exist in its current form, its founders say, is because they have partnered with large publisher Simon & Schuster for both distribution and printing – bringing production costs “back into the realm of possible” and smoothing “many of the road humps of distribution”.

Without a distributor, the publisher has to persuade individual booksellers to stock copies of a book, a model Aniko Press follows. This is highly labour-intensive, but does at least mean the publisher gets to keep that 30%.

Evercreech initially had a distributor, but it “fell through at the last minute”. Ouston’s background as a bookseller meant this was less of a hindrance than it might be for other new publishers: he knows how to sell his books to other booksellers. He told me this arrangement, while not ideal, is manageable at Evercreech’s size. “I like the hands-on, grass-roots element.”

In Australia, arts funding is in the bottom quarter of OECD countries as a share of GDP. While Writing Australia represents welcome new funding, the annual budget at a federal level for literature in 2025-26 administered through Creative Australia is $15 million according to a spokesperson from the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts. It is still a fraction of what it would take to safeguard the local industry.

If funding were available to better support publishing, it would be possible for more people from different backgrounds to start new publishers. Each of these new enterprises have valuable contributions to make to Australian publishing: but at the same time, it seems more than a coincidence that none of the founders identifies as being from a marginalised background.

A rare recent new venture in the Australian book industry with diverse founders is Marina Sano and Jing Xuan Teo’s Amplify Bookstore, which exclusively sells books by authors who are Black, First Nations and/or people of colour. Started as an online-only venture in 2020, a “pop up” bookshop opened in West Melbourne late last year.

Despite efforts such as the Open Book internship program and black&write!, the industry is still largely dominated by white people like me. Only a significant boost in government funding has a chance of changing that.

The emergence of new publishers is welcome news, following what seemed like a wave of conglomeration earlier in the year. But in a market of increasing costs, difficulties with distribution, waning literacy rates and in the face of the AI behemoth, their success is far from assured.