Move FM Australian News

The ANU is moving to kill the Australian National Dictionary – this is why it matters

Aug 8, 2025Share article

Print article

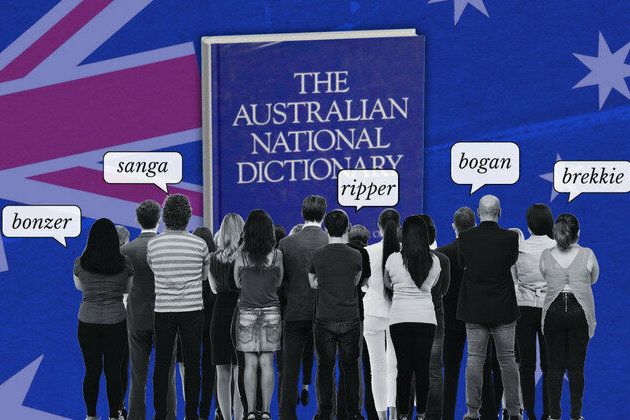

Bonzer. Dinkum. Troppo. We love our distinctive words and phrases.

We revel in the confusion they cause outsiders. We celebrate the stories behind them. We even make up a few furphies about them.

What many Australians might not know, however, is that for nearly 40 years a dedicated team at the Australian National University (ANU) has been hard at work digging up these past stories – real and furphy – and keeping a close eye on the new ones.

You’d be hard-pressed to find a more committed group of lexical patriots. Most everything you know, want to know, or have heard about Australian words comes from the Australian National Dictionary Centre (ANDC). From media, to academics, to everyday Aussies, we all rely on these quiet patriots – even if we don’t always know it.

But despite this work, and the central (and government-funded) role the ANU is meant to play in Australian history and identity, the ANU leadership is killing off the ANDC. The university has stated that the decision is a necessary part of reducing operating costs.

Dictionaries help define and reflect a nation’s identity. When Samuel Johnson published his famed Dictionary of the English Language in 1755, many celebrated that he and a handful of assistants accomplished in nine years what took 40 French academics half a century.

Dictionaries are especially important for colonial Englishes, such as those spoken in many countries, including Australia and the United States. At first, people looked down on these Englishes.

In the US, Noah Webster was derided for his suggestions Americans should assert their linguistic independence from Britain. US periodicals were openly hostile, jeering Webster’s “vulgar perversions” and “illiterate and pernicious” views of language.

However, when Webster’s American Dictionary of the English Language came out in 1828, it established the global importance of this new English. Mark Twain soon wrote,

The King’s English is not the King’s. It is a joint stock company and Americans own most of the shares.

Australia’s colonial English got off to a slow start – dismissed as “the base language of English thieves” and “crude, mis-shapen and careless“. But by the late 19th century, Australians began celebrating their distinct words, in the Bulletin, in books like Sidney Baker’s “The Australian Language”, and in dictionaries such as E.E. Morris’s “Austral Language”.

Still, many called for a truly national dictionary to capture the way Australians speak. Australian lexicographer Peter Davies wrote in 1975:

Vigorous cultures demonstrate pride and interest in their own languages and literatures by building great works in their honour.

Read more:

Get yer hand off it, mate, Australian slang is not dying

Finally, in the 1980s, Australians stopped taking their linguistic cues from Britain. With the publication of the Macquarie Dictionary in 1981 and the Australian National Dictionary in 1988, the language found its local voice.

However, these works differ in how they approach Australian English. The Macquarie Dictionary describes the spelling, pronunciation and definitions of English words as they are used in Australia.

The Australian National Dictionary (AND) grounds our words, and their meanings, in their historical and cultural contexts. The AND tells us where words have come from, when they were first used and how their meanings have changed over time. In short, the AND is a living, breathing and evolving record of how language is wrapped up in who we are as Australians.

As linguist Don Laycock once wrote, “there’s no other dictionary quite like this one in the world”. Its pages sing of “boundary riders, larrikins, sundowners, fizgigs, diggers and other dinkum Aussies”. Sidney J. Baker argued if the “Australian language [was] something to be reckoned with it” it was because of these iconic characters.

But the dictionary’s first editor, Bill Ramson, was not as romantic as Baker. Ramson wanted an academic and historical work – he left the romantic side of Australian English to the rest of us.

As an academic work, or more accurately, a monument to Australian English, the AND is unparalleled. Its second edition, released in 2016, contains the history of more than 16,000 words and phrases. Moreover, the second edition did the hard yakka to acknowledge the influence of Indigenous words on our English (words like “yakka”, from the Yagara language).

But the AND is more than an academic resource – its insights inform media, education and everyday life. We (the authors) write and speak widely about Australian English, with hundreds of media appearances each year, and we’ve both authored high school texts exploring its history and use. Howard Manns recently developed an SBS program introducing newcomers to Australian English.

Crucially, the AND’s research doesn’t just support this work – it makes it possible.

When the Australian National Dictionary was first published – by Britain’s Oxford University Press – some baulked at foreign involvement. In 1983, Australian publisher Kevin Weldon even called it “the most unpatriotic thing ever”, also objecting to it being edited by a New Zealander (Bill Ramson) and an English woman (Joan Hughes).

History, of course, has vindicated them – and the many others, Australian or not, who helped create this cultural landmark.

But Weldon was not necessarily wrong. In the end, it seems American-style managerialism will be the death of the ANDC. Weldon surely didn’t anticipate that the “most unpatriotic thing ever” – the killing off of the AND – would be an act by Australians at the Australian National University.

In a statement, the ANU told The Conversation: “This decision reflects the need to reduce recurrent operating costs while ensuring that core academic activities are sustainably embedded within Schools and Colleges”.

Cutting the ANDC isn’t just a short-sighted administrative decision to save a few quid. It’s the wilful disregard of Australian cultural heritage and the powerful work its scholars do to help us understand the past, present and future of Australians, our English and our identities.

This dictionary centre is a national asset – once it’s gone, we lose a living record of our national voice.